Abstract

Objects

There is a scarcity of data regarding childhood neurological injuries in developing countries such as Nepal. The epidemiology of acute pediatric neurotrauma in Kathmandu was studied to assess the implications of these data for injury prevention programs.

Methods

The clinical records of patients ≤18 years who presented to Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital between April 1, 2001 and April 1, 2004 with acute neurological trauma and were subsequently admitted to hospital were retrospectively reviewed. A standard proforma was used to collect information on patient demographics, the nature and etiology of the injuries, their acute management, and outcomes.

Conclusions

Four hundred sixteen injured children were admitted to hospital, and the charts for 352 (85%) were available for review. Spinal injuries were relatively rare (4%) compared to head injuries (96%). Falls were the most common cause of injuries (61%). It took significantly longer (p<0.001) for children injured in rural Nepal (62%) to obtain neurosurgical care (30.1 h) than those injured within Kathmandu (7.1 h). A Glasgow Outcome Score of 5 was obtained for 96%, 76%, and 22% of patients with mild, moderate, or severe head injuries, respectively. Besides efforts to improve prehospital transport and acute management of these injuries, preventive measures that are applicable to the Nepalese scenario are urgently needed. Interventions should focus on health education programs directed at parents and children and upgrading of road safety measures. Neurological injuries must also be viewed in the context of the broader social issues in Nepal that contribute to injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Injuries are a significant cause of childhood morbidity and mortality, especially in developing countries where two thirds of injury deaths occur [1]. The Global Burden of Disease Study estimates that 10% of global deaths are due to injuries and predicts that trauma and infectious diseases will account for equal amounts of potential life lost worldwide by 2020 [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that 98% of all child injury mortality occurs in the world’s poorest countries, and the rate of these deaths is five times higher than among industrialized nations [2]. The magnitude of the problem is even greater considering that for every death there are thousands of nonfatal injuries that result in lost disability-adjusted life years. Children in developing countries are especially vulnerable to injury due to challenging living conditions, increasing road traffic, lack of safe play areas, and absence of childcare options [2].

Neurological injuries are one of the most common types of trauma for which children are admitted to hospital [3, 4], and their long-term sequelae may alter children’s full participation in the community [5]. Approximately 75% of children admitted to hospital with injury have a head injury [4], and 70% of injury deaths are due to head injuries [6]. In industrialized countries, traumatic brain injuries affect 191/100,000 children annually, and the recognition that neurological injuries are associated with more death and disability than all other pediatric problems combined [7] has prompted calls for increasing research attention to neurotrauma [8].

There is a scarcity of data regarding such injuries in developing countries, like Nepal. The perception exists among neurosurgeons in Nepal that a large proportion of their clinical activities is trauma related, and, consequently, there is a high incidence of injury-related disability (Shilpakar and Sharma, personal communication, June 2004). Comprehensive information about regional neurotrauma epidemiology is necessary for planning management strategies and intervention priorities that can respond effectively and appropriately to local conditions [9–12] and is recognized by the WHO [13] as a key priority for strategic research. The objective of this study was to describe the epidemiology of pediatric neurological injuries presenting to Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), an urban hospital in Nepal, and to assess the implications of this data for injury management and control programs.

Methods

Setting

This study was set in Nepal, one of the economically poorest countries in the world. Although a modern health care system was introduced to Nepal in the 1950s, Nepal still has among the worst health indicators in South Asia, with the government spending only 5.2% of its gross domestic product and US $63 per capita annually on health care [14], compared to 13.9% and US $4,887 in the United States [15]. Forty-four percent of the country’s population is under 15 years of age [16]. TUTH is a 411-bed nongovernment-run tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu that serves a local population of more than one million people and receives patients from the entire 24 million population of Nepal. It is only one of a few tertiary care centers in the country, most of which are clustered in the Kathmandu Valley, and one of three that offers neurosurgical services. Patients needing neurosurgical treatment are managed as indicated on the 18-bed ward, 5-bed surgical intensive care unit, or 6-bed intensive care unit.

Case ascertainment

The clinical records of children aged 18 years or younger who presented to TUTH Casualty Department between April 1, 2001 and April 1, 2004 with acute neurological trauma and who were subsequently admitted to the neurosurgical service or died before admission were retrospectively studied. Patients declared dead on arrival to the Casualty Department were excluded because their clinical information was limited and only recorded in the Casualty Department records.

Neurological injuries were identified on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 diagnostic codes. Cases selected for review included mild head injuries: cranial fractures with no specified cranial injury (ICD-9: 800.0, 800.5, 801.0, 801.5, 803.0, 803.5, 804.0, 804.5), concussions with no loss of consciousness or with loss of consciousness for less than 1 h (ICD-9: 850.0 and 850.1), concussions with unspecified lengths of time of loss of consciousness that were nonfatal and incurred hospital stays shorter than 10 days (ICD-9: 850.5 and 850.9), and nonfatal unspecified cranial injuries with no loss of consciousness or with loss of consciousness for less than 1 h that incurred hospital stays shorter than 10 days (ICD-9: 854.0, 854.1, 800.4, 800.9, 801.9, 803.4, 803.9, 804.4, and 804.9); major head injuries: cerebral lacerations (ICD-9: 851.0–851.9, 800.1, 800.6, 801.1, 801.6, 803.1, 803.6, 804.1, and 804.6), cerebral hemorrhages (ICD-9: 852.0–852.5, 853.0, 853.1, 800.2, 800.3, 800.7, 800.8, 801.2, 801.3, 801.7, 801.8, 803.2, 803.3, 803.7, 803.8, 804.2, 804.3, 804.7, 804.8), and unspecified cranial injuries with loss of consciousness for 1 h or longer that incurred hospital stays of 10 days or longer and were not attributable to other injuries (ICD-9: 854.0, 854.1, 800.4, 800.9, 801.9, 803.4, 803.9, 804.4, and 804.9); spinal injuries: spinal cord injuries (ICD-9, 806.1–806.9, 952.0–952.9), spinal fractures without cord injuries (ICD-9, 805.1–805.9), and dislocated vertebrae (ICD-9: 839.0–839.59); and peripheral nerve injuries, including injuries to the nerve roots and spinal plexus (ICD-9: 953.0–953.9). Cases were found by reviewing the operative database maintained by the neurosurgeons at the hospital that records clinical details of all the patients who have undergone neurosurgical procedures since the service began in February 1996, the neurosurgery ward admission log books, and the hospital’s medical records database in which all inpatient charts are coded in accordance with the ICD-9.

A standard proforma was used to collect information on patient demographics, the nature and etiology of the injuries, and their acute management and outcomes. All neurotrauma data were collected by one worker (KM), who used information from physicians’, nurses’, and physical therapists’ notes. Mechanisms of injury were grouped and subgrouped as falls, road traffic incidents, assault, and other (unspecified and miscellaneous). Prehospital care was categorized as to whether the children were treated first at local health posts or other hospitals prior to being referred to TUTH. Head injuries were graded according to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and spinal injuries according to the American Spinal Cord Injury Association (ASIA) grading scale. Functional outcome at the time of discharge for head-injured patients was categorized using the Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS). Frequencies, one-way analysis of variance, and Bonferroni’s post hoc test were used to describe the data.

Results

During the study period, 416 children were admitted to the neurosurgical service with acute traumatic neurological injuries. Of these patients, 64 (15%) did not have enough information regarding diagnosis or treatment recorded in the inpatient charts to be included in the analyses of results.

Demographics

Of the 352 patients whose medical information was complete enough for analyses, 228 (65%) were boys. Neurological injuries were more common in school-aged children (68%), peaking for those in elementary school (Table 1).

Circumstances of injuries

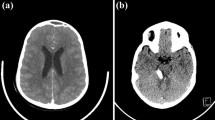

The most common type of injury requiring admission to the neurosurgical service was mild head injury (GCS 14 or 15) (57%). Other injuries included moderate head injuries (GCS 9–13) (26%), severe head injuries (GCS<8) (13%), and spinal injuries (4%). Most (47%) spinal injuries involved lumber fractures, while 35% were due to cervical trauma. The proportion of patients presenting with ASIA grades A, B, C, D, and E was 24, 6, 12, 29, and 24%, respectively. Two patterns of injury were recognized on radiographic studies: vertebral fractures (59%) and subluxation (6%). The remaining patients with spinal injuries had unspecified injuries. No patients were admitted with peripheral nerve trauma.

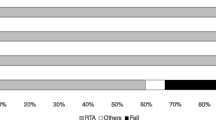

Falls were the leading cause of injuries overall (61%) and in all age groups (Fig. 1, Table 1). Most falls occurred from a height of one storey or 8 to 10 feet (50%) (Fig. 1b). Road traffic incidents were responsible for an increasing proportion of neurological injuries among school-aged children (Table 1) compared to children less than 5 years of age. Most children involved in road traffic incidents were pedestrians (51%), usually in transit to or from school (Fig. 1c). Assault, including reported child abuse, was an uncommon etiology of injury occurring in 1% of children. Other causes of injury (8%) included occupational injuries, natural disasters, or falling objects.

a Etiologies of pediatric neurotrauma. b Subgrouping for road traffic incidents, including children injured as pedestrians, while riding bicycles, and as occupants of motor vehicles, and c falls, including children injured during falls from ground level or from one (8 to 10 feet) or more storeys (>10 feet)

Injury management

Most children (62%) sustained their injuries outside of the Kathmandu Valley. Local health posts outside of the Kathmandu Valley initially saw 5% (19) of injured children, while hospitals either within or outside of the Kathmandu Valley saw 56% (197) prior to being referred to TUTH. Kanti Children’s Hospital, the country’s only tertiary care pediatric hospital located adjacent to the Tribhuvan University medical school and TUTH, saw 24% (86) of the children prior to referring them to TUTH.

Neurosurgical treatment was significantly delayed (p<0.001) for those children who sustained their injuries outside of the Kathmandu Valley (Fig. 2). Children injured within the valley took approximately 8 h to obtain neurosurgical attention at TUTH after their injury, and there was no statistically significant difference in the time it took children to reach TUTH based on the type of injury that they sustained (p>0.05). In contrast, children who sustained head injuries outside of the Kathmandu Valley took more than 1 day to reach TUTH, and those with spinal injuries took more than 8 days.

Most imaging for neurological injuries was done once the patients were admitted to TUTH. Few children, even with severe head injuries, had any imaging performed outside of TUTH. For example, 88% to 94% of children with head injuries received a brain computed tomography (CT) scan at TUTH, whereas only up to 4% of children received such imaging at another hospital. At those hospitals, skull x-rays were a more commonly employed imaging modality, performed in up to 30% of patients. Children with spinal injuries had CT (24%) and magnetic resonance imaging (18%) of the spine performed exclusively at TUTH. Plain x-rays of the spine were performed for 82% of these patients at TUTH and 42% at another hospital.

Similarly, medical management of traumatic injuries was mainly done once patients arrived at TUTH. Osmotic therapy, antiepileptics, antibiotics, and steroids were administered to 18, 32, 37, and 6% of patients respectively on admission to TUTH, whereas only 8, 14, 10, and 6% of patients received these medications at the other hospitals. Only 12% of patients with spinal cord injuries arrived at TUTH in time to receive methylprednisolone treatment.

Operative procedures for pediatric trauma comprised 16% of the neurosurgery service’s pediatric caseload, second only to shunt procedures for hydrocephalus (36%), and 7% of the service’s overall operative caseload during the study period. Of the 55 children who underwent neurosurgery, craniotomies were the most commonly performed procedure (44%), followed by elevation of depressed skull fractures (22%), and irrigation and debridement of wounds (16%). Although spinal injuries comprised only 4% of the patients in the series, spinal decompression and instrumentation procedures made up 15% of all the operations performed. Instrumentation was done using Luque rods made of Rush pins and sublaminar wires. Only 3% of children had ventriculostomies performed for intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring and therapeutic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage.

Length of stay in hospital increased with severity of head injury and was longest for those children with spinal injuries. There was a statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in the mean amount of time children with mild (5 days) or moderate head injuries (10 days) remained in hospital compared to those with severe head injuries (18 days) or spinal injuries (26 days).

Injury outcomes

Enough information was available in the inpatient records to ascertain the GOS for 231 (66%) of the head-injured children (Fig. 3). Most children with mild or moderate head injuries had a good outcome (96% and 76%, respectively) (GOS 5). Twenty-two percent of children with severe head injuries had a good outcome, while 28% died (GOS 1). Because children injured outside the Kathmandu Valley were shown to take a significantly longer time to reach TUTH than those injured within the valley, the GOS for patients injured in those two locations was also analyzed (Fig. 3b,c). Again, most children with mild head injuries had a GOS of 5, regardless of the location where their injuries were sustained. However, fewer children sustaining moderate head injuries outside of the valley had such a good outcome: 69% for those injured outside the valley compared to 87% for those injured within. For children with severe head injuries sustained within the valley, a larger proportion had either a good outcome (GOS 5) (40%) or died (GOS 1) (30%) (Fig. 3b); for the others, there was a more uniform distribution of proportions of children across the GOS outcomes (Fig. 3c).

Although arrangements for follow-up post-discharge in the Neurosurgery Outpatient Department (OPD) were made for 276 (78%) of the patients, only 49 (18%) were ultimately seen in follow-up, almost half of whom lived in Kathmandu.

Discussion

Injuries traditionally have been under-recognized as a significant cause of childhood death and disability in developing countries, where infectious diseases and nutritional problems have been perceived as the major causes of death [1, 2]. The WHO estimates that the expenditures per year of life lost from death and disability in developing countries were only US $0.06 for trauma, whereas those for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and malaria were US $3.89 and $1.31, respectively [17]. Given the economic challenges facing the health systems of many of these countries, injury prevention efforts are a cost-effective way of dealing with the problem of childhood injuries. In outlining the four steps necessary to implement any public health intervention, Krug and colleagues [18] note that the first of these steps is to determine the scale, scope, and character of the problem. This study represents to the best of our knowledge the only recent examination of the epidemiology of pediatric neurological injuries in South Asia and therefore forms an important basis for the development of injury prevention programs not only for Kathmandu, but perhaps also for other urban South Asian centers.

Study caveats

Prior to drawing inferences on neurotrauma management and prevention from our study, we must acknowledge its limitations. Like other hospital-based studies, our study likely underestimates the true magnitude of the problem of children’s neurological injuries because patients with mild injuries may have sought medical attention, but were not admitted to hospital, and formal health facility use in many developing countries has been reported to be low. For example, a community-based study in Ghana found that only 31% of fatal injuries received formal medical care [19]. In Nepal, an alternative for many patients to hospital-based care is that offered by traditional healers, who are much more accessible in rural communities than physicians [20–22]. Indeed, a recent survey in Nepal found that patients with epilepsy were as likely to seek medical attention from traditional healers as from physicians [21]. Community and population-based studies provide a more complete understanding of the nature of the neurotrauma problem by better representing etiologies, types, and severities of injuries in broader segments of society [2, 19]. In addition, the patient population seen at TUTH, a nongovernment hospital in which patients must pay for all clinical services, may be different than that seen at the other major neurosurgical service in Nepal at Bir Hospital, the country’s oldest tertiary care center at which the fees for services are more subsidized.

Injury management

It is of concern that it takes children who incur severe head injuries outside of the Kathmandu Valley an average of 30 h to reach TUTH from the time of injury, and even those injured within the valley take about 8 h to get to this neurosurgical center. This delay in obtaining neurosurgical attention clearly has implications for outcome, since recent scientific, evidence-based documents report that improvements in outcome can be achieved by prompt resuscitation and transport of patients to dedicated trauma centers [3, 6, 23–26]. Interestingly, our study found that the proportion of children who died due to head injuries was higher for those injured within the Kathmandu Valley (32%) compared to those injured outside of the valley (20%), although it took the latter children on average more than three times as long to reach TUTH (Fig. 3b,c). This may be because more children injured in rural Nepal may have died before arriving to TUTH than those injured within the valley.

Obtaining neurosurgical care for children in Nepal, particularly in rural areas, is logistically difficult. Travel to TUTH from outside of the Kathmandu Valley can mean a journey of several days to the nearest airstrip or bus stop; from there, the road journey to the capital may take another day or two [27]. Ongoing political and civil unrest in Nepal, which has resulted in road blocks, frequent road security checks, and violence, has also delayed and, in some cases, precluded patients’ travels to Kathmandu’s hospitals [28–35]. These challenges may explain the low proportion of children with neurological injuries who returned to the Neurosurgery OPD for follow-up (18%). Alternatively, many patients may have sought follow-up care at their local hospital or one of the other hospitals in Kathmandu offering neurosurgical services, may have died from complications of their injury before being able to see a physician, or may have been well enough that they deemed follow-up unnecessary.

Partly, as well, this delay in transport to hospital may be due to the lack of a prehospital emergency medical services system in Nepal, as is the case in many developing countries [19, 36, 37]. Although ambulances exist in Nepal, they have no equipment other than a stretcher and a first aid box for wound dressings. Moreover, ambulance drivers have no training in emergency trauma care since ambulances tend to serve as interhospital patient transport vehicles and rarely collect children from the scene of injury. Injured children are invariably brought to hospital by their relatives, bystanders, or police and frequently conveyed in inappropriate transport facilities. Since the current infrastructure, telecommunications systems, and funds for the establishment of formal emergency medical services systems are limited in Nepal, an alternative to reduce pediatric neurotrauma morbidity and mortality may be to build on the existing informal prehospital transport systems, as has been done in other developing countries [36]. For example, in Ghana, a program providing basic first aid training to commercial drivers increased the provision of first aid at the site of injury [38, 39]. In Kurdistan and Cambodia, the creation of a two-tier emergency response system that involved injury first responders with first aid training and paramedics with more advanced training as secondary responders was found to reduce the death rates for those with severe injuries from 40% to 9%, although the existing patient transport system that relied on commercial vehicles and nonmotorized transport was used [40].

Even if injured children are able to make it to TUTH for neurosurgical care, the cost of this treatment can be expensive for many parents in Nepal. Almost no medical insurance exists in Nepal, which means that families are expected to bear all of the costs of treatment for neurotrauma. These costs begin the moment the child is seen in the Casualty Department, with a ticket to see the physician costing US $0.20. Admission to one of the neurosurgical units costs US $1.00 daily if only a ward bed is required, but as much as US $8.50 daily if monitoring in the intensive care unit is required. A brain CT costs US $36. Operative procedures such as craniotomies or spinal decompression and instrumentation cost US $36 and $43, respectively. Added to these costs are those of any medications or medical supplies. Given that the gross national income per capita is only US $238 [41] compared to US $35,182 in the United States [15] and that almost half of the population lives below the poverty line [14], it is not surprising that even these costs are expensive for many parents, requiring them to sell land or borrow money. That the costs of medical treatment are prohibitive for families is demonstrated by recent studies from Nepal that show that poverty was one of the main factors precluding obtaining treatment for cataracts and cleft lip and palate [42, 43].

Improvements in hospital-based care in Nepal are likely to improve pediatric neurotrauma outcomes. Most of the children in this series (61%) were initially managed at a local health post or hospital prior to being referred to TUTH. Only a minority of patients, even with severe injuries, had medications administered in these settings; for example, children were more than twice as likely to receive osmotic therapy at TUTH than at the other health centers. Similarly, few patients had any brain or spinal imaging performed prior to referral to TUTH. This reflects the human and physical resource constraints of hospitals outside of the Kathmandu Valley. There may only be one physician for an entire district of 200,000 people [27, 33], health posts may not be staffed by physicians, and health care staff may not have any specific training in injury care. The hospitals’ use of electrical generators means these sometimes-unreliable sources of electricity make x-ray machines and even oxygen concentrators unavailable [27]. Other hospitals in developing countries [44, 45] have lowered rates of injury-related deaths through low-cost hospital-based improvements. In Trinidad, for instance, certifying physicians at the main hospital in the Advanced Trauma and Life Support course lowered death rates of severely injured patients from 40% to 9% [44, 45].

Interventions to improve hospital-based care are relevant not only for the referral hospitals but for TUTH as well. Few patients in our series (3%) had ventriculostomies performed and, as is the case for most other neurosurgical centers in South Asia [46], ICP monitoring is not routinely done at TUTH. However, Joseph [46] describes an economical, accurate, and safe system for both ICP monitoring and therapeutic CSF drainage that has been used successfully in the Indian context and is likely equally applicable to the Nepalese one. Thus, improving neurosurgery in developing countries does not necessarily imply the need to acquire unaffordable technologies. Indeed, Ramamurthi [47], who had more than 50 years of neurosurgical experience in India, has cautioned against assuming that progress in neurosurgery is dependent on the adoption of these technologies. As the experience in Nepal demonstrates, it is possible for neurosurgeons to be trained in modern techniques and with the latest equipment and still perform quality neurosurgery with local resources and basic equipment [48–50].

Injury control

Given the challenges facing the provision of neurosurgical care for injured children in Nepal, efforts to prevent neurological injuries should be made in concert with those to improve their management. Although injuries are frequently regarded as random events [51–53], they are, for the most part, predictable and thus controllable. Injury death rates in countries associated with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development have decreased by 50% over the past couple of decades due to the combination of advances in transport systems and housing construction and efforts in the realms of education and legislation [2, 54]. Mock and colleagues [54] argue that this has been possible also because of the application of scientific principles to injury prevention.

Consistent with reports from other developing countries [55–57], falls are the most common cause of neurological injuries among children presenting to TUTH and are thus an important target for injury prevention programs. It is not surprising that most (92%) of the children were injured from falls of at least 8 to 10 feet, frequently at home, given the architectural landscape of Nepal (Fig. 4a). Houses commonly feature flat-top roofs without fences and high windows without any protection. Studies in middle-income countries of central Asia have found that these home environments are risk factors for falls [57, 58]. For example, in suburban Jordan, a survey of mothers of young children found that 25% of the houses surveyed exposed children to the risk of falls, and in 33%, children used the unsafe roofs for play [57]. Interviews with mothers of children less than 5 years of age in a Brazilian squatter settlement found that risk factors for falls included not only the children’s physical environment, but social factors as well, including the amount of time mothers, as primary caregivers, spent working out of the house [59].

a Given the architectural landscape of much of Kathmandu, it is not surprising that falls are a common etiology of pediatric neurotrauma. b Although road traffic has been progressively increasing over the past two decades in Kathmandu, some progress in injury control has been made with the construction of road safety facilities, such as zebra crossings and pedestrian walkways

Fall prevention programs in Nepal should be directed at both parents and children and should address the need for safe play areas for children and greater supervision and child care options. In addition, one-time home environmental modifications that may be more effective to implement than those that require behavioral change may also be applicable to the Nepalese scenario [60]. In New York City, awareness in the 1970s of the importance of falls in injuries and deaths led to the introduction of a program that installed window guards in apartment buildings [61]. Window guards, regulations limiting the spacing between balcony rails, and modifications to limit window opening have been associated with a reduction in falls [60].

Injury prevention programs in Nepal should also address road traffic, which was identified in this study as the other major etiology of pediatric neurotrauma. Road traffic incidents are the ninth leading cause of global loss of health life measured in terms of disability-associated life years [1]. In other developing countries, such as Ghana [62], Nigeria [63], and Uganda [64], traffic is the leading cause of injury death. This reflects these countries’ more advanced phase of economic development, which is characterized by increasing motorization, compared to Nepal, which is still only in its early phase [65]. A recent study by Poudel-Tandukar and colleagues [65] suggests, however, that road traffic injuries are poised to become a more prominent injury etiology. In Kathmandu, traffic-related deaths have been steadily increasing since 1981, likely due to the city’s increasing population size and rapid growth of traffic volume, which has increased from 76,000 registered vehicles in 1989 to 1990 to 355,000 in 2001 to 2002 [65].

The journey to and from school represents a high risk for traffic injury for Nepalese children. Schools are clearly an entry point for road safety education programs, since most children injured in road traffic incidents in our study were school aged and pedestrians. Children also commonly sustained injuries as passengers in vehicles. In Nepal, the cheapest and most common forms of transport, such as buses and three-wheel taxis, do not have any safety restraints. Because bus drivers are often paid according to the number of passengers they carry, public transport is frequently overloaded with passengers sitting on the roofs or hanging out of the doors. Some progress has been made in terms of road safety in Kathmandu with the legislation of mandatory helmet use while riding motorcycles and the construction of pedestrian zebra crossings and walkways, widening of roads, and installation of traffic lights (Fig. 4b). Poudel-Tandukar and colleagues [65] are still concerned that the pace of installation of such safety facilities may not be able to keep up with the traffic volume that is expected to further increase with Nepal’s economic development.

Successful implementation of pediatric neurotrauma prevention programs depends on the context in which they are applied as well as their content [53, 66]. In Nepal, this means, as Bartlett [2] and others [53, 67] have warned, that prevention strategies successful in developed countries may not be appropriate because they are unaffordable or reliant on systems that are unavailable. As well, considering that almost half of the population of Nepal lives below the poverty line [14], neurotrauma must be understood in the context of poverty, which is both a risk factor for injury [67] and related to communities’ efforts to prevent injury [68].

Conclusions

Pediatric neurological trauma represents a significant public health problem, and interventions to manage and prevent these injuries should be a priority in Nepal. The findings of this study describe the situation mainly of Kathmandu, but may reflect the problems faced in other large South Asian cities and will help to plan health services for pediatric neurotrauma more accurately.

It is of concern that it takes some even severely injured patients more than a day to obtain urgent neurosurgical services. No prehospital emergency medical services system exists in Nepal, and children are frequently brought to TUTH by relatives in inadequate transport facilities. Referral hospitals receive a large proportion of childhood injuries, yet are usually insufficiently staffed and lack the resources to provide initial medical management and diagnostic imaging. Even at TUTH, ideal management of neurological injuries is sometimes hindered by a lack of hospital resources and patients’ poverty that makes aspects of neurosurgical care unaffordable.

Besides efforts to improve prehospital transport and acute management of these injuries, preventive measures that are applicable to the Nepalese scenario are urgently needed. Interventions should focus on health education programs directed at parents and children and upgrading of road safety measures. Neurological injuries must also be viewed in the context of the broader social issues in Nepal that contribute to injury, such as poverty and increasing political and civil unrest.

References

Murray CJ, Lopez AD (1997) Mortality by cause for eight regions of the world: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349:1269–1276

Bartlett SN (2002) The problem of children’s injuries in low-income countries: a review. Health Policy Plan 17:1–13

Ghajar J (2000) Traumatic brain injury. Lancet 356:923–929

Lam WH, Mackersie A (1999) Paediatric head injury: incidence, aetiology and management. Paediatr Anaesth 9:377–385

Schwartz L, Taylor HG, Drotar D, Yeates KO, Wade SL, Stancin T (2003) Long-term behavior problems following pediatric traumatic brain injury: prevalence, predictors, and correlates. J Pediatr Psychol 28:251–263

Faillace WJ (2002) Management of childhood neurotrauma. Surg Clin N Am 82:349–363

Arias E, MacDorman MF, Strobino DM, Guyer B (2003) Annual summary of vital statistics—2002. Pediatrics 112:1215–1230

Albright AL (2004) The past, present, and future of pediatric neurosurgery. J Neurosurg (Pediatrics) 101:125–129

Allhouse MJ, Rouse T, Eichelberger MR (1993) Childhood injury: a current perspective. Pediatr Emerg Care 9:159–164

Bernstein E, Kellerman AL, Hargaten SW, Jui J, Fish SS, Herbert BH, Flores C, Caravati ME, Krishel S (1994) A public health approach to the twenty-first century. Acad Emerg Med 1:277–286

Manciaux MR (1985) Accidents in childhood: from epidemiology to prevention. Acta Pediatr Scand 74:163–170

Waxweiler RJ (1994) Public health, injury control, and emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 1:204

World Health Organization (1996) Investing in health research and development: report of the ad-hoc committee on health research relating to future intervention options. Geneva, Switzerland

World Health Organization (2004) Country profiles: Nepal. http://www.who.int/countries/npl/en. Accessed 19/9/2004

World Health Organization (2004) Country profiles: United States of America. http://www.who.int/countries/usa/en. Accessed 27/12/2004

UNICEF (2004) At a glance: Nepal. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/nepal.html. Accessed 27/12/2004

Michaud C, Murray CJ (1994) External assistance to the health sector in developing countries: a detailed analysis, 1972–90. Bull World Health Organ 72:639–651

Krug EG, Sharma GK, Lozano R (2000) The global burden of injuries. Am J Public Health 90:523–526

Mock CN, nii-Amon-Kotei D, Maier RV (1997) Low utilization of formal medical services by injured persons in a developing nation: health service data underestimate the importance of trauma. J Trauma 42:504–513

Poudyal AK, Jimba M, Murakami I, Silwal RC, Wakai S, Kuratsuji T (2003) A traditional healers’ training model in rural Nepal: strengthening their roles in community health. Trop Med Int Health 8:956–960

Rajbhandari KC (2004) Epilepsy in Nepal. Can J Neurol Sci 31:257–260

Streefland P (1985) The frontier of modern western medicine in Nepal. Soc Sci Med 20:1151–1159

Brain Trauma Foundation (2000) Guidelines for the prehospital management of traumatic brain injury. Brain Trauma Foundation, New York

Brain Trauma Task Force (2000) Management and prognosis of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 17:451–553

Johnson DL, Krishnamurthy S (1996) Send severely head injured children to a pediatric trauma center. Pediatr Neurosurg 25:309–314

Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Maier RV, Grossman DC, MacKenzie EJ, Moore M, Rivara FP (2001) Relationship between trauma center and outcomes. JAMA 285:1164–1171

Ibbotson G (2003) Nepal: a lesson from chaos. CMAJ 169:1301–1304

British Broadcasting Corporation (2004) Concern over Nepal rebel threat. http://www.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/3540866.stm. Accessed 18/8/2004

British Broadcasting Corporation (2004) Strike continues to cripple Nepal. http://www.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/3703743.stm. Accessed 19/9/2004

British Broadcasting Corporation (2004) Rebels cut links to Nepal capital. http://www.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/4119951.stm. Accessed 23/12/2004

British Broadcasting Corporation (2004) Nepal violence ‘leaves many dead.’ http://www.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/4121885.stm. Accessed 23/12/2004

Jimba M, Wakai S (2001) Is Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence dead in Nepal? Lancet 358:1017–1018

Singh S (2004) Impact of long-term political conflict on population health in Nepal. CMAJ 171:1499–1501

Stevenson PC (2001) The torturous road to democracy—domestic crisis in Nepal. Lancet 358:752–756

Stevenson PD (2002) High-risk medical care in war-torn Nepal. Lancet 359:1495

Hauswald M, Yeoh E (1997) Designing a prehospital system for a developing country: estimated costs and benefits. Am J Emerg Med 15:600–603

Razzak JA, Luby SP, Laflamme L, Chotani H (2004) Injuries among children in Karachi, Pakistan—what, where and how. Public Health 118:114–120

Forjuoh S, Mock CN, Freidman D (1999) Transport of the injured to hospitals in Ghana: the need to strengthen the practice of trauma care. Pre-hosp Immed Care 3:66–70

Mock CN, Tiska M, Adu-Ampofo M, Boakye G (2002) Improvements in prehospital trauma care in an African country with no formal emergency medical services. J Trauma 53:90–97

Husum H, Gilbert M, Wisborg T, Van Heng Y, Murad M (2003) Rural prehospital trauma systems improve trauma outcome in low-income countries: a prospective study from North Iraq and Cambodia. J Trauma 54:1188–1196

World Bank (2004) Nepal data profile. http://www.worldbank.org/cgi-bin/sendoff.cgi?page=/data/countrydata/aag/npl_aag.pdf. Accessed 9/19/2004

Schwarz R, Khadkha SB (2004) Reasons for late presentation of cleft deformity in Nepal. Cleft Palate-Craniofac J 41:199–201

Shrestha MK, Thakur J, Gurung GK, Joshi AB, Pokhrel S, Ruit S (2004) Willingness to pay for cataract surgery in Kathmandu valley. Br J Ophthalmol 88:319–320

Ali J, Adam R, Butler AK, Chang H, Howard M, Gonsalves D, Pitt-Miller P, Stedman M, Winn J, Williams JI (1993) Trauma outcome improves following the advanced trauma life support program in a developing country. J Trauma 34:890–898

Ali J, Adam R, Stedman M, Howard M, Williams JI (1994) Advanced trauma life support program increases emergency room application of trauma resuscitative procedures. J Trauma 36:391–394

Joseph M (2003) Intracranial pressure monitoring in a resource-constrained environment: a technical note. Neurol India 51:333–335

Ramamurthi B (2004) Appropriate technology for neurosurgery. Surg Neurol 61:109–116

Bagan M (1997) Neurosurgery in Nepal. Surg Neurol 47:512–514

Devkota UP, Aryal KR (2001) Result of surgery for ruptured intracranial aneurysms in Nepal. Br J Neurosurg 15:13–16

Shilpakar SK, Bagan M (2003) Surgical management of traumatic epidural hematoma: over seven years experience. JSSN 6:33–39

Meyer AA (1998) Death and disability from injury: a global challenge. J Trauma 44:1–12

Tursz A (1986) Epidemiological studies of accident morbidity in children and young people: problems of methodology. World Health Stat Q 39:257–268

Zwi AB (1996) Injury control in developing countries: context more than content is crucial. Inj Prev 2:91–92

Mock C, Quansah R, Krishnan R, Arreola-Risa C, Rivara F (2004) Strengthening the prevention and care of injuries worldwide. Lancet 363:2172–2179

Adeloye A, Olumide AA, Obiang HM (1986) Acute head injuries in children in Ibadan, Nigeria. Childs Nerv Syst 2:309–313

Gedlu E (1994) Accidental injuries among children in north-west Ethiopia. East Afr Med J 71:807–810

Janson S, Aleco M, Beetar A, Bodin A, Shami S (1994) Accident risks for suburban pre-school Jordanian children. J Trop Pediatr 40:88–93

Yagmur Y, Güloğlu C, Aldemir M, Orak M (2004) Falls from flat-roofed houses: a surgical experience of 1,643 patients. Injury 35:425–428

Reichenheim ME, Harpham T (1989) Child accidents and associated risk factors in a Brazilian squatter settlement. Health Policy Plan 4:162–167

Istre GR, McCoy MA, Stowe M, Davies K, Zane D, Anderson RJ, Wiebe R (2003) Childhood injuries due to falls from apartment balconies and windows. Inj Prev 9:349–352

Spiegel CN, Lindaman FC (1977) Children can’t fly: a program to prevent childhood morbidity and mortality from window falls. Am J Public Health 67:1143–1147

Abantanga FA, Mock CN (1998) Childhood injuries in an urban area of Ghana: a hospital based study of 677 cases. Pediatr Surg Int 13:515–518

Shokunbi T, Olurin O (1994) Childhood head injury in Ibadan: causes, neurologic complications and outcome. West Afr J Med 13:38–42

Kobusingye OC, Guwatudde D, Owor G, Lett RR (2002) Citywide trauma experience in Kampala, Uganda: a call for intervention. Inj Prev 8:133–136

Poudel-Tandukar K, Nakahara S, Poudel KC, Ichikawa M, Wakai S (2004) Traffic fatalities in Nepal. JAMA 291:2542

Pokhrel S, Sauerborn R (2004) Household decision-making on child health care in developing countries: the case of Nepal. Health Policy Plan 19:218–233

Berger LR, Mohan D (1996) Injury control: a global view. Delhi, India

Roberts I, Power C (1996) Does the decline in child injury mortality vary by social class? A comparison of class specific mortality in 1981 and 1991. BMJ 313:784–786

Acknowledgements

K.M. gratefully acknowledges the support of the Foundation for International Education in Neurological Surgery that sponsored travel to Kathmandu and Dr. Merwyn Bagan and Dr. Richard Perrin who facilitated K.M.’s Volunteer for International Neurosurgical Education experience in Nepal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mukhida, K., Sharma, M.R. & Shilpakar, S.K. Pediatric neurotrauma in Kathmandu, Nepal: implications for injury management and control. Childs Nerv Syst 22, 352–362 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1235-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-005-1235-0